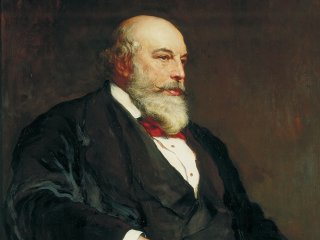

Sir William Armstrong (1810 – 1900)

The Magician of the North

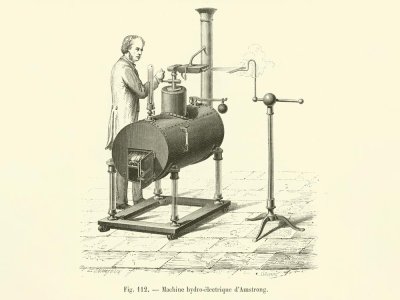

Tower Bridge’s original steam engines raised the bascules over 400,000 times before they were replaced in the 1970s. The technology behind this marvel of Victorian engineering was based on an invention by one of the world’s most successful industrialist-engineers, William Armstrong.